We all have our blind spots, but when the spots are small and secretive we might be forgiven them. At Wintu Audubon’s general meeting last month, Ken Sobon, director of the Northern Saw-whet Owl Project, introduced attendees to a much overlooked little predator that could well be the most numerous owl in North America.

It’s not exactly invisible, but even avid bird watchers are unlikely to have seen this puffball. Daytimes it hides away, roosting quietly in thick foliage, remaining still even as you pass right by. At night you might hear it, especially if you get out into our local coniferous forests. This time of year males begin their long-running nocturnal too-too-too calls, which can beckon a female from half a mile or more away. If interested, she carols back with her own songs–high squeaks or a rising wail that is music to his ears. He may then sing and circle her many times before alighting at her side.

The male often shows her a cavity that he thinks will make a good nest–perhaps a hole carved in a snag by a large woodpecker, with a nearby meadow for hunting. Of course, she seems to make the final decision on just where she will lay her half-dozen eggs. That nest will be her station for the roughly forty-five days of incubation and early child care.

Like raptors around the world, she begins incubating as soon as the first egg is laid, so her young hatch not all at once, as chickens do, but over a period of a week or more. If food is plentiful, all the young may survive; the male may even support two mates and two nests. If food is scarce, however, only the older siblings are apt to successfully fledge.

He hunts every night. From a low perch in the quiet of the forest, he listens for the rustling of small rodents, and then swoops down. He kills with the piercing clutch of his talons. He is scarcely the size of a man’s fist, and the mice and voles he captures can easily weigh half as much as he does. But he ferries the load to the nest where, if the eggs have not yet hatched, the delivery may serve as both a hot meal and left-overs for later.

After her youngest is two and a half weeks old, and the oldest is almost ready to start exploring nearby branches, the female will leave the nest and either assist in hunting for the young, or she may move on to find a new mate and nest a second time. The male continues to feed the nestlings for at least another month.

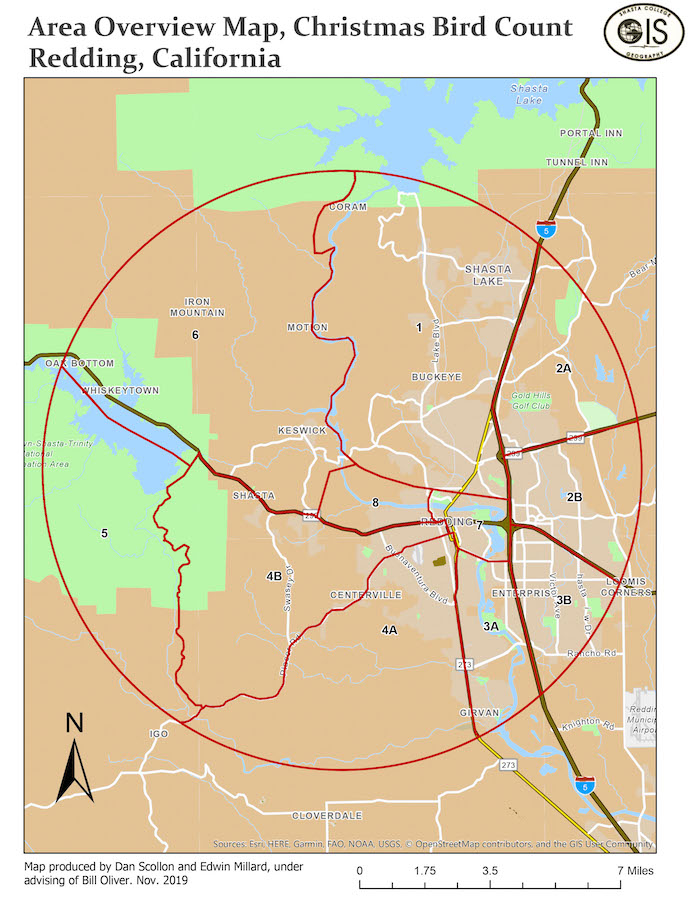

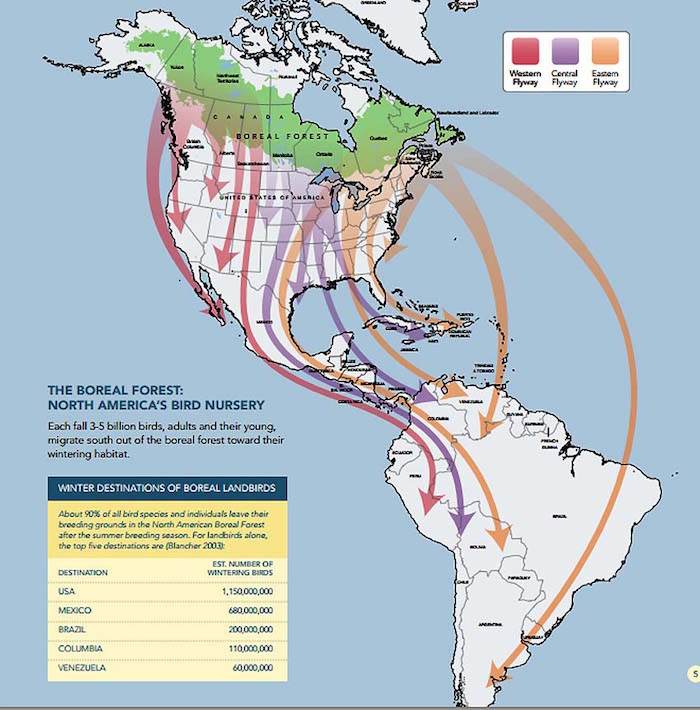

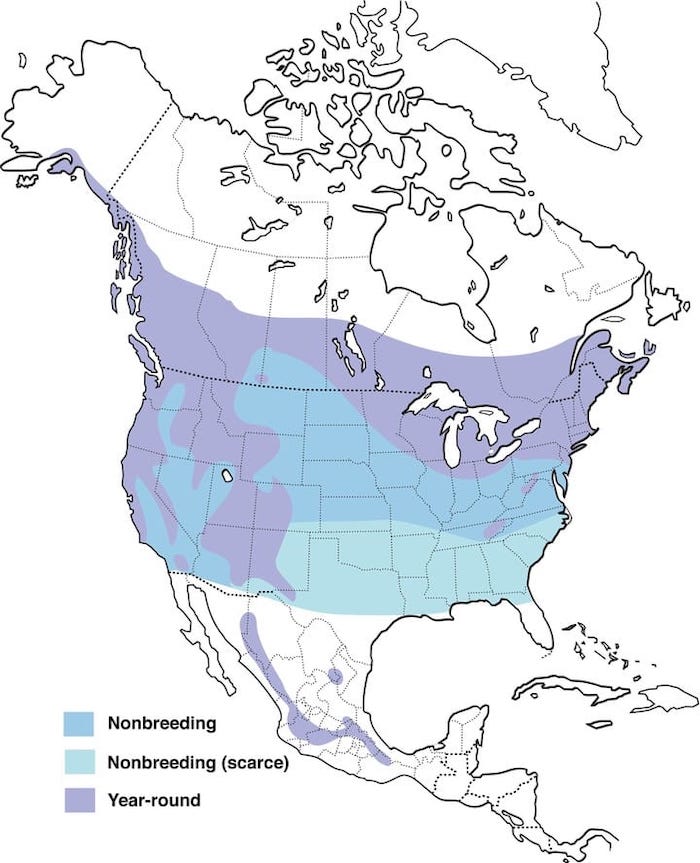

Saw-whets span North America coast to coast. Our locals appear to migrate along the west coast, but they freely travel east-west, too. They nest in our forests and parts north, well into Canada, where they are apt to retreat if American forests continue to suffer as expected from climate disruption.

As for their name, it is another of their mysteries. It supposedly recognizes a similarity in the sound of saw-sharpening and the owl’s vocalization, but that match eludes most of us.