It’s a team sport. It’s parallel play. It’s research. It’s art. It’s an exercise in hope. It’s a long cold day outdoors!

The tradition of Christmas Bird Counts was begun by Frank Chapman in 1900. People often do things because they don’t know what else to do, and Chapman wanted to provide an alternative to the then-popular Side Hunts—Christmas Day competitions to kill and gather the biggest pile of furred and feathered animals. It was the era when John Muir was chastising Teddy Roosevelt for expressing his love of animals by shooting them, and when the Audubon Society had recently formed to dissuade people from killing egrets so their plumes could adorn ladies’ hats. The Bird Counts quickly caught on.

From that first rudimentary count in 1900, in which 25 areas from Massachusetts to Pacific Grove, CA were surveyed by 27 people to tally a total of 90 species, the annual count has grown into a massive inventory of Western Hemisphere birds. Some 75,000 people now identify and count all the birds they can in over 2500 established circles. The circles are 15 miles in diameter. The counts are held between December 14 and January 5. Good-weather years can yield 60 million birds in over 2600 species.

Locally, bird watchers conduct four Counts. The oldest, the Redding Count, was begun in 1975. It extends from Shasta College through most of Whiskeytown Lake, and from Shasta Dam down to South Bonnyview Road. Up the road, the Fall River Count was established in 1984, and is always popular as a location where valley, mountain, and Great Basin species can be found in its open fields and abundant waterways. South of Redding, the Anderson and Red Bluff Counts abut each other where the temperate Central Valley provides winter homes to numerous songbirds and waterfowl.

Together, the four counts this year hosted 81 people covering a total of 109 miles on foot, 939 miles by car, and 13 miles by kayak or canoe to tally 165 species and 75,712 individual birds.

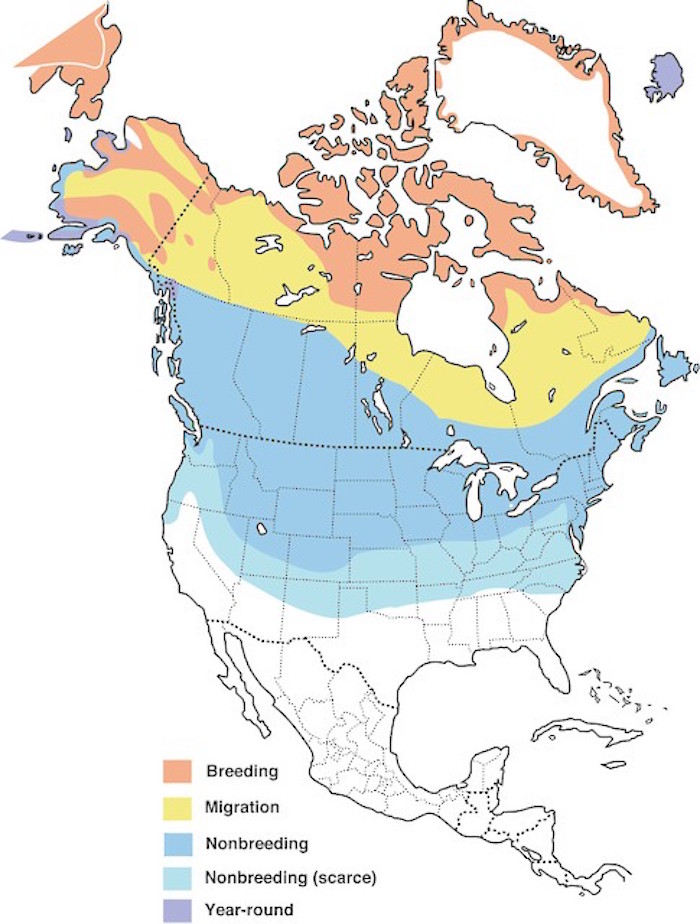

There are always some rarities on the counts, but this year had many. In addition to a wayward swamp sparrow from the eastern US, and a handful of mute swans, who are elegant but destructively ravenous invasives, the rare birds mostly seem to reflect warm weather. Kayakers on Redding’s stretch of the Sacramento River found a black-throated gray warbler and a Hammond’s flycatcher, both of whom are expected to be sunning in Mexico this time of year. A boater in Fall River found a red-breasted merganser and a red-necked grebe, who usually winter in temperate coastal waters. A burrowing owl in Anderson, and Red Bluff’s sage thrasher and white pelican are all pushing their wintering range northward.

Perhaps the warm weather, holding some southland birds here, is also keeping many of our traditional birds away, farther north. Fall River compiler Bob Yutzy reports, “The numbers of most species were down.” Low numbers are repeated throughout the North State. Brooke McDonald’s report on the Anderson count includes “We had 18 Mallards, which is shockingly low. The average is 132 and the previous low was 81. We had 25 robins and the average is 201.”

From Red Bluff Michele Swartout reports, “We have had little precipitation so far this winter season, which meant very little to no water in our local ponds and wetlands. The lack of waterfowl, in both species and quantities was very obvious during this year’s count.”

Bill Oliver, compiler of the Redding count, sums up his findings: “The species total was a high average, but the number of [individuals] was below average, as it has been for the other local Counts.”

While the ecological disruptions of a warming climate cannot be welcome, we can hope that for now our missing North State birds are temporarily elsewhere, perhaps discovered in other counts. National Audubon is compiling the data and, if wet weather doesn’t bring the birds in sooner, will be able to let us know before long.