Sometimes the garden is not quite right. Coronavirus and the other horsemen are trampling the flowers, and the misshapen economy will make next year’s seeds a stingier find. And even then, you may not be able to grow much because of climate change. Is there any help beyond Netflix and sedation?

Yes: bird-watching. It’s accessible, versatile, and beautiful. And a whole lot healthier than couch-bingeing.

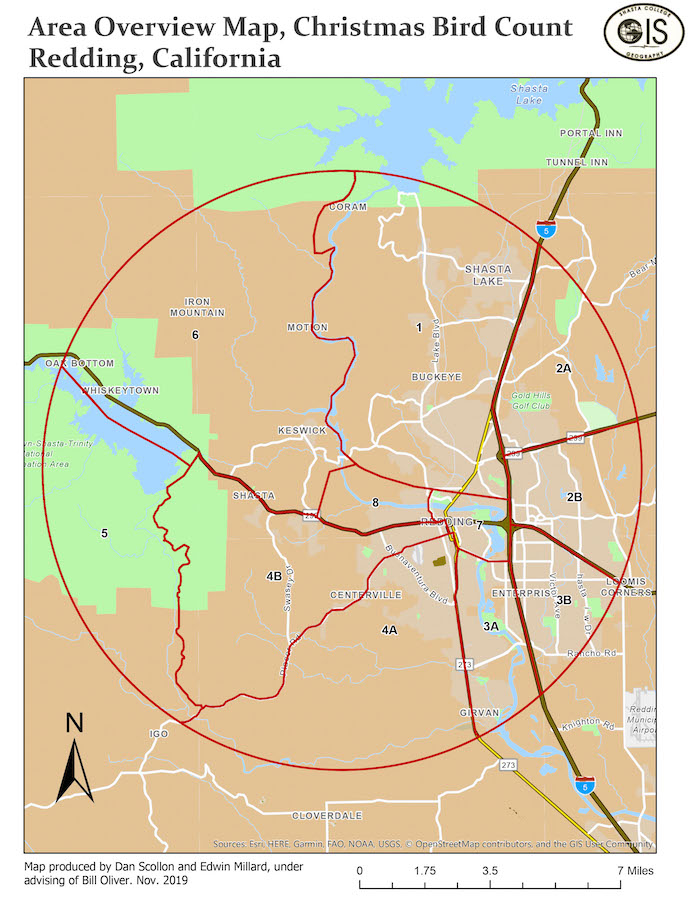

But how do you start? Local Audubon activities are shut down, but the website, wintuaudubon.org, remains a rich resource. I’ll highlight a few and put them in context.

First, where can you watch birds? Since you’re at home, that can be an excellent place. If there are trees and shrubs around, then you are apt to find a variety of birds. You can put out feeders to attract them into a handy viewing area. For information on feeders and seed, click on the website’s “Attracting Birds” under the “Places to Bird” tab. For your own good viewing, or if you have children under, say nine, who can’t yet handle binoculars, then consider putting the feeders up close to a window. Window collisions are killers, but if feeders are placed within three feet of the window then slower flight speeds around the feeder make harmful collisions rare.

Of course, don’t expect the birds to be tidy. And recognize that, depending on your local traffic, it may take birds some weeks to find your feeders. But then the word will spread.

If you’re able to get outside, birding can enrich your walk. Here in the North State we have numerous parks and trails that support both wildlife viewing and physical distancing. Turtle Bay, Mary Lake, Clover Creek, and the Sacramento River Trail are among the in-town birding hotspots. Again, see the “Places to Bird” tab for more information.

You’ll need a pair of binoculars. Without them you will not see the rich colors of the birds. Fortunately, optics have improved in recent years, and excellent binoculars are available at reasonable prices–sometimes better prices than the reviews indicate. I recommend starting with the “How to Choose Your Binoculars” article under the “Get Outside/Binocular Guide” tab at audubon.org. It gives a straight scoop on quality, usefulness, and price. Then read reviews and shop.

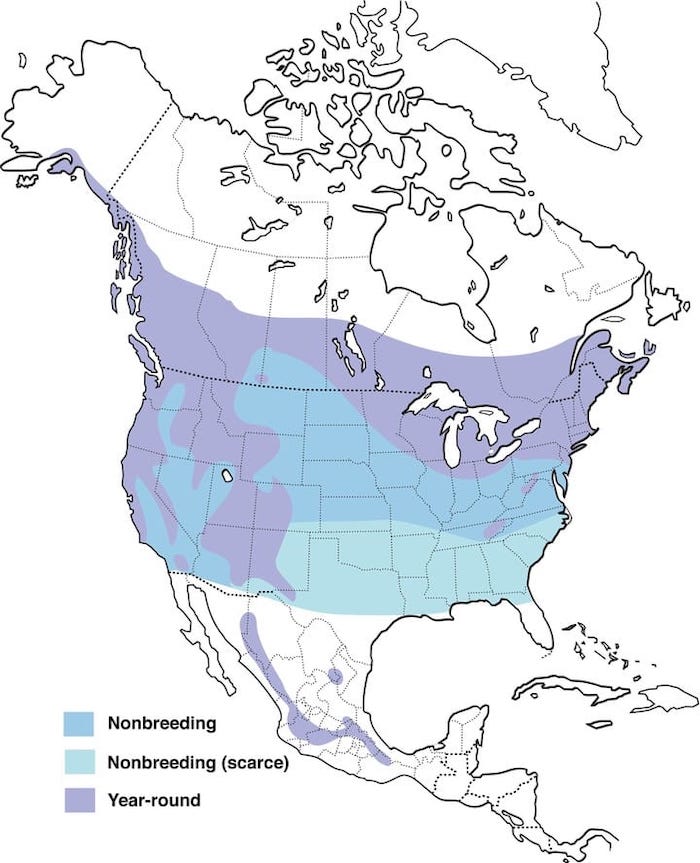

At home or on a walk, it’s nice to be able to know what you are seeing. Scroll down the right column of the Wintu Audubon home page to find the Shasta County Bird Checklist. This printable list shows the seasonal abundance of our birds. For another useful resource, you may want to download the Merlin app, which uses the date, your location, and your answers to just a few questions to identify the bird.

Of course, bird watching is more than bird identification. Close observation can reveal what a bird eats, how it gathers its food, whether it has a nest nearby, how it is taking care of itself, or how it gets along with its neighbors. The website allaboutbirds.org can feed your understanding with species by species information about the birds.

Wintu Audubon hopes to be running programs and bird walks again this fall. In the meantime, binoculars, a field guide or online app like Merlin, perhaps a feeder, and some time let us see a world that is at least as real as the one sinking us into the couch.