Goldeneyes grow up in Canada, but you don’t need to fly to Great Slave Lake to see them. They’ll fly here instead!

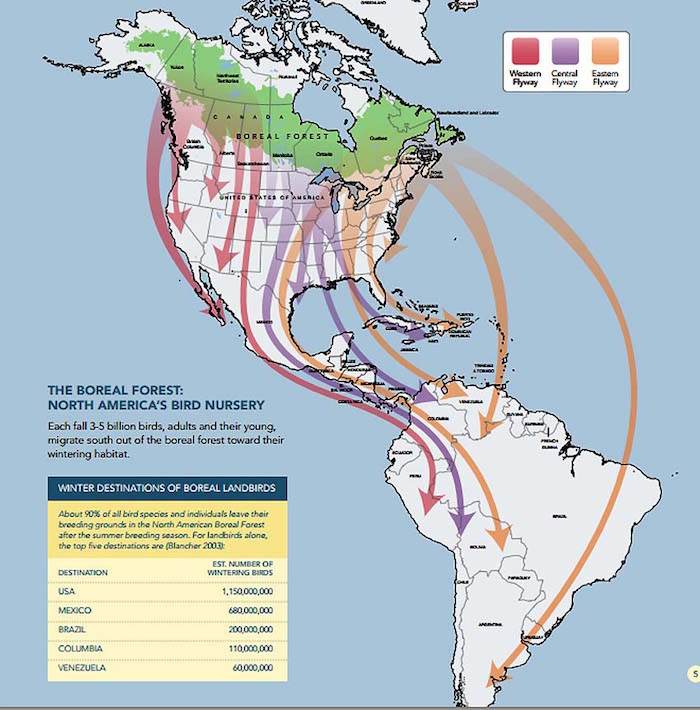

After a long summer of little more than mallards on our waterways, now is the season of ducks returning like rain to the North State. To the delight of Thanksgiving hunters, bird-watchers, and children at Kutras Pond, the colors, quacks, and squeals of many duck species are returning to the North State. The goldeneyes, like so many ducks that nest in the vast Canadian forests or in the midcontinent prairie potholes, are heading south from their nesting grounds to what they need–open water that won’t freeze over.

In our area they can be seen on the river, readily identifiable by–well, you can guess their eye color! The males, or drakes, have black backs, white sides, dark heads with a green cast, and, between their black bill and bright eye, a bold white spot. The hens forego that white beauty mark, but wear a tip of yellow on their bill; they replace bright white flanks with nest-camo gray, and the sheen of their head feathers is cinnamon-burgundy.

Goldeneyes are cavity nesters, making homes in trees near boreal waters, using the large holes formed by pileated woodpeckers or by limbs ripped from their trunks by wind or time and decay. As in several duck species, new hatchlings tumble two or more stories from nest to ground, pop up no worse for wear next to their waiting mother, and follow her to the local lake or river.

That walk can be a long one. Unlike mallards, goldeneyes are diving ducks. Their legs, situated farther back on their bodies, facilitate power and agility under water, but make land travel a stilted, more unsteady endeavor. Still, both the young ones and their mothers do what they must to accommodate reality, and make the trek from nest to water.

There they are all at home. The day-old ducklings begin to feed themselves, starting a lifestyle of diving for underwater invertebrates and small fish in both calm and rippling waters. The hen goldeneye may protect her babies, but the ducklings readily attach to a foster-mom for oversight, too.

In their first fall they will fly south to winter in the US, and the next spring will wing back to their boreal home. Apparently they are starting to fly farther north than they used to, following the forests that around the globe are retreating northward due to logging, mining, and climate change.

Logging for paper products opens the land to further warming as exposed permafrost melts. Turning trees into toilet paper has become a widespread concern. Among locally available products Seventh Generation, Green Forest, Trader Joe’s regular (not SuperSoft), and Natural Value–generally the less gentle product lines–get high marks for using recycled content rather than virgin forest in their toilet paper.

Mining for fossil fuels also exposes permafrost, and its intended product is the source of 76% of our climate change emissions.

And climate change itself kills boreal forests by supporting beetle infestations, drying the forest, increasing fire susceptibility, and reducing the winter chill needed for new tree growth.

Goldeneyes are part of the circumpolar constriction toward the North Pole that the whole boreal forest is undergoing. In the coming decades of unrestrained climate change, they are expected to winter farther north and their gold will become rarer in the Lower Forty-eight.