Black swifts are birds of mystery. We know they’re fast, probably powering to over 100 mph. We know they’re fliers, apparently spending up to ten months a year in flight. But much that is known or speculated about them is based on only a few observations, so uncertainty is also part of our understanding.

Like the Redding eagles, black swifts seem comfortable, or at least unconcerned, with having people around; but unlike the eagles, their “around” doesn’t include downtown. They do their living in out-of-the-way places, and even there they are unobtrusive neighbors. They nest in dark crevices of waterfall or oceanside cliffs; they forage high above us, and never perch on wires or trees where we can see them; and they utterly neglect to announce themselves with colorful displays or loud songs. They are small, black-brown birds that flit by with the speed of their name, and their light chittering song is often lost to our ears in the roar of nearby water. They are variously reported as having stable local populations and as having declined 94% over the last fifty years.

But here in the North State they give us this much: they nest at Burney Falls. Each spring, for longer than our history can testify, black swifts make their way to the torrent, where they build and repair nests in the protected nooks among braids of tumbling water. Working with mud and moss, they fashion a hand-sized crib, palm up to cradle their single egg. In the soggy damp of the falls, the egg will take four weeks to hatch, twice as long as most birds their size. Then, with continuing slow development, the chick will not fledge for another month and a half.

It is at nest-sites that we can best observe these wide-ranging birds. Both parents incubate and tend the young. There are reports of adults roosting near the nest while their mates warm the baby. But those are the only documented reports of these birds landing at all.

Swifts are in the family Apodidae, meaning those without feet. In fact, their feet and legs are reduced, capable of catching cliffside toeholds, but incapable of standing, perching upright, or walking. It is said that if they ever landed on the ground they would not be able to take off again. They go into flight by dropping from their cliff-hold.

Once airborne, however, they are in their element. They zip through the air, often in loose flocks, catching and eating insects on the wing, often higher up than we can see them. They drink water by skimming open-billed at the surface of a lake or pool. They apparently mate on the wing, and almost certainly sleep in the air. Studies on oceanic frigatebirds show that some birds can sleep one hemisphere of the brain at a time–a sleep schedule that seems unappealing, but beats staying awake for ten months!

When young black swifts fledge, they have no trial flights. Most songbird fledglings flutter weakly and hide and rest, gradually building their flight muscles. But swifts are immediately on their way, catching insects and winging–where?

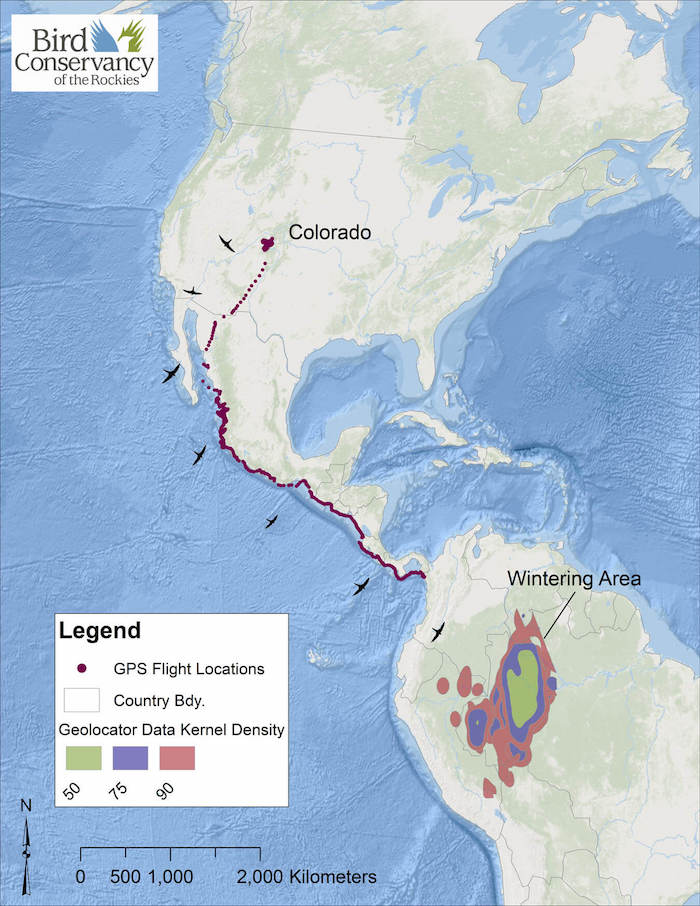

They will fledge in July. By September they are out of Shasta County. By mid-October they are out of the country. Until 2012 we could only guess where they went. That year researchers using ultra-light geolocators studied black swifts from Colorado. They learned that those swifts winter in the lowland rainforest of western Brazil, a land rich in vegetation and the flying insects these birds need.

Maybe our Burney Falls black swifts winter there, too. But we don’t know. They haven’t told us yet.