Meet trip leader Sally NeSmith (831-535-2888) at the Carl & Leah McConnell gate (Arboretum Drive off of North Market) for a meander through the Arboretum, over the Sundial Bridge and back along the river trail. Acorn Woodpeckers, Anna’s Hummingbirds, towhees, some raptors, and warblers are always present. We’ll look for early fall migrants and check out the waterfowl along the river.

Tag: birds

Family/Beginner Bird Walk at Turtle Bay

We invite beginners of all ages to our introductory walks on the first Saturday of each month. The walks begin at 9am and meet in the parking lot near the Monolith structure at the end of the Sheraton Hotel. Binoculars and field guides will be available to loan. Call Terri Lhuillier, 515-3504, for more information.

Listen for a Nasal Beeping in Your Neighborhood Trees

In the bird world of the North State, there’s little that’s more common than a nuthatch. You’ll find more avian tonnage in winter refuges and flooded fields, and you’ll find brighter plumages and louder songsters. But nuthatches are year-round decorations in our native trees.

You can scarcely go for a walk up in the fir belt without hearing the tiny red-breasted nuthatches. These little cuties may be tough to see as they pick small insects from high-up in the conifers, but their quick, nasal ankh-ankh-ankh-ankh-ankh calls can be relentless and ubiquitous as they keep in touch with one another.

Down in the oak woodlands, the larger, teacup-sized white-breasted nuthatches fill the woods with calls that are similar but a touch more mellow, slower and lower.

The white-breasteds are often easily viewable, as they usually forage not in twig-tip foliage but on the open expanse of exposed trunks and large limbs. Also helpful for viewing, the oaks are shorter than firs, and many will later lose their leaves. With their regular calling and white faces that stand out against dark trunks, white-breasted nuthatches are one of the most visible little birds in the trees. When flying away, they may flash more white at the corners of their tails. You may be able to see their blue-gray backs, and, in the males, their nape and crown darkened to a rich blue-black.

But it is nuthatch behavior that really stands out. Most birds are like us–our feet are down and our heads are up. But nuthatches give the world a different look. Their regular habit is to fly high and work their way down a trunk. They pick for insects in bark fissures, and the down-trunk approach gives them a view into crevices that woodpeckers and other gleaners miss. Perhaps that less common world view helps lead to their success. These nuthatches are widespread across North America.

Their visibility can be enhanced in your own yard, especially if nearby you have some of the big old oaks they favor. Nuthatches will frequent feeders, especially those offering sunflower seeds. Unlike finches and sparrows, they dine take-out style. They will select a seed and fly away with it. If you can follow their flight, you may see them wedge the seed into some bark, either for later consumption or to hold it there as they bang at it with their bills to “hatch the nut” out! They will nest in cavities of old limbs or in nesting boxes that you can place in your yard.

Nuthatches lay a half dozen or more eggs each spring, and their populations have increased over the last fifty years. They are expected to remain regular winter residents of the North State, but are likely to move north for breeding as they deal with climate change.

Swift and Secret

Black swifts are birds of mystery. We know they’re fast, probably powering to over 100 mph. We know they’re fliers, apparently spending up to ten months a year in flight. But much that is known or speculated about them is based on only a few observations, so uncertainty is also part of our understanding.

Like the Redding eagles, black swifts seem comfortable, or at least unconcerned, with having people around; but unlike the eagles, their “around” doesn’t include downtown. They do their living in out-of-the-way places, and even there they are unobtrusive neighbors. They nest in dark crevices of waterfall or oceanside cliffs; they forage high above us, and never perch on wires or trees where we can see them; and they utterly neglect to announce themselves with colorful displays or loud songs. They are small, black-brown birds that flit by with the speed of their name, and their light chittering song is often lost to our ears in the roar of nearby water. They are variously reported as having stable local populations and as having declined 94% over the last fifty years.

But here in the North State they give us this much: they nest at Burney Falls. Each spring, for longer than our history can testify, black swifts make their way to the torrent, where they build and repair nests in the protected nooks among braids of tumbling water. Working with mud and moss, they fashion a hand-sized crib, palm up to cradle their single egg. In the soggy damp of the falls, the egg will take four weeks to hatch, twice as long as most birds their size. Then, with continuing slow development, the chick will not fledge for another month and a half.

It is at nest-sites that we can best observe these wide-ranging birds. Both parents incubate and tend the young. There are reports of adults roosting near the nest while their mates warm the baby. But those are the only documented reports of these birds landing at all.

Swifts are in the family Apodidae, meaning those without feet. In fact, their feet and legs are reduced, capable of catching cliffside toeholds, but incapable of standing, perching upright, or walking. It is said that if they ever landed on the ground they would not be able to take off again. They go into flight by dropping from their cliff-hold.

Once airborne, however, they are in their element. They zip through the air, often in loose flocks, catching and eating insects on the wing, often higher up than we can see them. They drink water by skimming open-billed at the surface of a lake or pool. They apparently mate on the wing, and almost certainly sleep in the air. Studies on oceanic frigatebirds show that some birds can sleep one hemisphere of the brain at a time–a sleep schedule that seems unappealing, but beats staying awake for ten months!

When young black swifts fledge, they have no trial flights. Most songbird fledglings flutter weakly and hide and rest, gradually building their flight muscles. But swifts are immediately on their way, catching insects and winging–where?

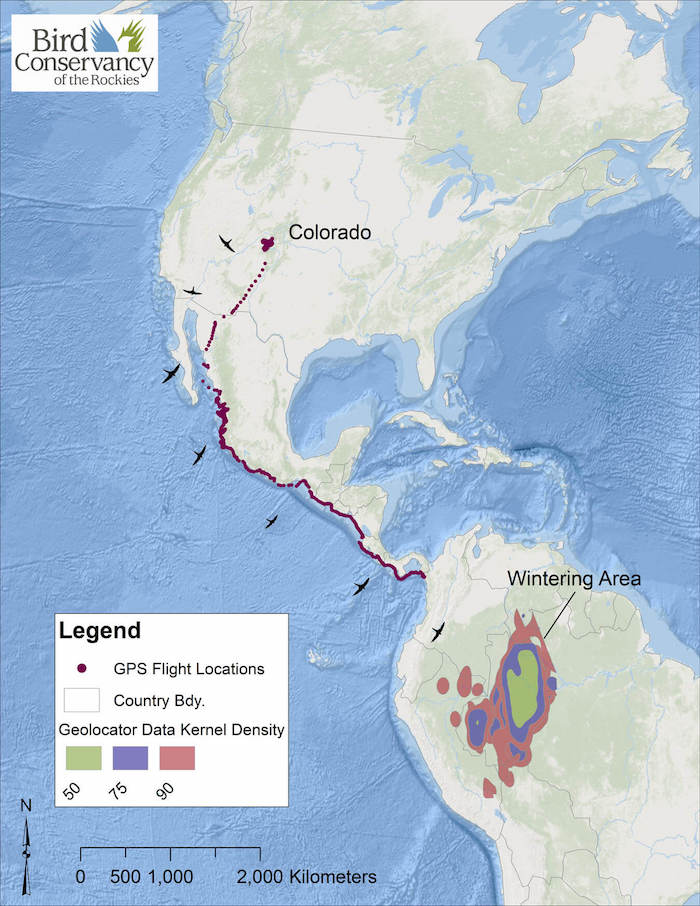

They will fledge in July. By September they are out of Shasta County. By mid-October they are out of the country. Until 2012 we could only guess where they went. That year researchers using ultra-light geolocators studied black swifts from Colorado. They learned that those swifts winter in the lowland rainforest of western Brazil, a land rich in vegetation and the flying insects these birds need.

Maybe our Burney Falls black swifts winter there, too. But we don’t know. They haven’t told us yet.

Local Weekday Bird Walk at the Turtle Bay Arboretum

Meet trip leaders Sally NeSmith & Ashley Byers (831-535-2888) at the Carl & Leah McConnell gate (Arboretum Drive off of North Market) for a meander through the Arboretum, over the Sundial Bridge and back along the river trail. Several types of Woodpeckers, Towhees, Goldfinches, and Warblers will be observed as well as the nesting Osprey family. Red-shouldered Hawks, Wood Ducks and the Common Yellowthroat may be present.