Nature with its feathers and its viruses does not dance for our pleasure or pain. Water does not need us to make a river. But we, of course, can both minimize natural suffering and enjoy natural beauties.

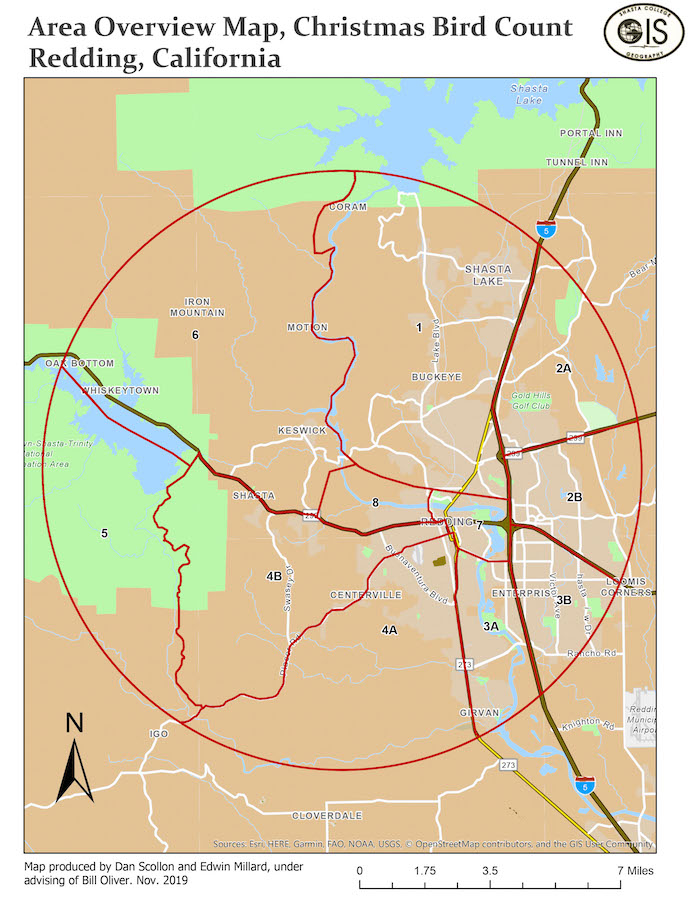

There are uncounted bright spots freshly arrived in northern California. Spring blooms deck our yards and fields, and, in the bird world, subtropical migrants have returned, decked in their finest plumage.

Among the brightest are orioles. Bullock’s oriole males sport brilliant orange breasts and faces; their topside is mainly black, including an onyx cap, eyeline, and chin, with contrasting bright white patches on their wings. Females are yellow breasted, fading to a whitish belly; their backs are pale brown–the pale colors that help hide them and their nests, and so keep the species going.

And these beauties dance. When I was six years old I was given a package of plastic animals, each about my pinky-length. The mammals were cast in brown, the birds in blue. In less than a day I lost my instant favorite, the wily weasel. Gradually I lost the others, roughly in order of how much I valued and therefore played with them. The last to go was a clunky blue thing identified as an oriole.

It did the orioles injustice. They are not clunky. The uniform blue I could allow; it was the color of the plastic, and I knew nothing different. But its statue-stiff stance belied the birds’ reality. More accurately, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology opens its description of these orioles with the word “nimble.”

Orioles are nimble in so many ways. Our Bullock’s orioles dangle from the swaying tips of cottonwood and valley oak branches and weave there the hanging baskets that will hold their eggs and nestlings. They glean insect meals from those same precarious twigs–or from larger branches, or trunks, or from spider webs, or brush on the ground. They are versatile, and also resourceful. If they catch a bee, they’ll pull and discard the stinger before dining. If they catch a toxic butterfly, such as a monarch or pipevine swallowtail, they’ll bang it on a branch to extract just the insides and avoid the poisons stored in the butterfly’s skin. Or they’ll eat fruit, creating juice by piercing the skin and opening their bills inside, and then lapping the mushy liquid with their long tongues. Or they’ll use those tongues at hummingbird feeders, where a modest perch and a broken-out floret can invite repeat visits.

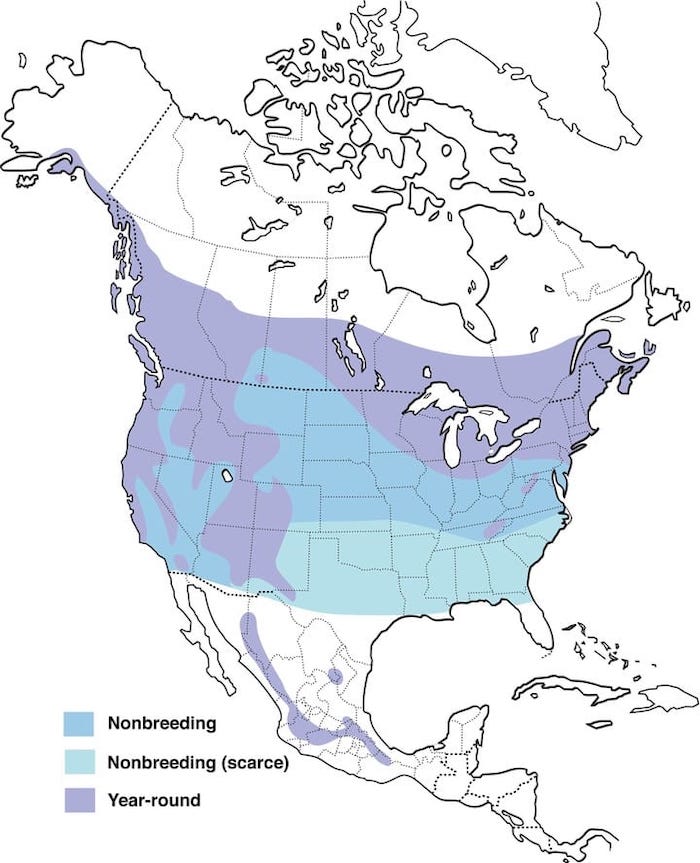

Their flexibility extends even to their human association and naming. For a while Bullock’s orioles had been lumped into a single species with Baltimore orioles; the two do hybridize where their ranges meet in the Great Plains. Further studies, however, have separated them back into the two species that their different color patterns had originally suggested.

Besides being brilliant and nimble, these birds are fast. To see them, listen for their harsh chatter mixed with melodious squeaking, and keep an eye to your taller trees. Perhaps you will find one of their twig-end nests, a hanging basket the size of a big orange. After two weeks of incubation, both parents will tend the nestlings there, offering ready views of some of nature’s brightest beauties.