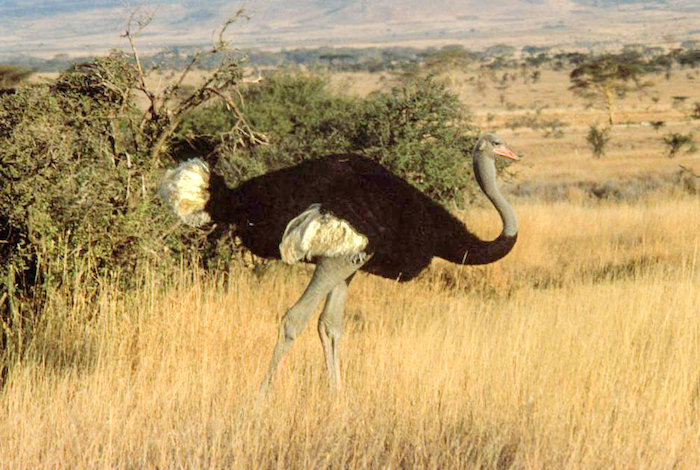

The ten thousand species of birds in the world come with tremendous variety. The ostrich can stand nine feet tall, tip the scales at 280 pounds, and run at over forty miles per hour. The bee hummingbird is less than two and a half inches long, weighs one twentieth of an ounce, and can’t run at all, or even walk.

A red-breasted merganser flew even with a plane at an air speed of over 80 mph, ground speed over a hundred. Peregrine falcons stooping on prey have sped to at least 186 mph. Hummingbirds can hover in place, a flight achievement of zero mph.

The engine of a plane in Africa sucked in a Ruppell’s griffon vulture–at an altitude of 36,100 feet! Penguins “fly” only under water. New Zealand’s kiwi has stubby little wings, perhaps as useful as a T-rex’s hands; it cannot fly.

Killdeer nest in open flats, maybe gathering just a couple pebbles to mark the site. Orioles weave hanging baskets of plant fiber or other debris. Cliff swallows build with mud, swiftlets use saliva, and hummingbirds gather and form lichen and spider webs. Kingfishers nest in tunnels they dig, as much as eight feet into the ground. Emperor penguins’ feet serve as nests. Eagles build with sticks, adding more as they re-use the nest over years and generations; a nest in Florida was 9.5 feet across, 20 feet deep, and estimated to weigh over two tons. Gyrfalcons in Greenland use a cliff nest that is 2500 years old.

Osprey flap over water looking for fish to catch. The thick-billed murre has been found swimming 690 feet under water.

Goatsuckers and owls wear camouflage feathers that blend into the gray-brown bark they press against. Tanagers, orioles, and honeycreepers blaze brilliant colors with stunning richness and iridescence.

All this variety of behavior and physical features is the result of the distinctive habitats that grace our planet. The diverse opportunities, requirements, and happenstance of survival hone the qualities of plumage, flight, size, color, and nest building, as well as the shape and strength of feet and bills, flocking behavior, and everything else about the birds.

The thing about these adaptations is that they do not just permit living a certain way in a certain habitat; they require it. An eagle can’t catch flies from the air to have its dinner. A woodpecker can’t paddle like a duck and skim algae off the water. Like all living things, birds need the habitat they are designed for.

But now the world is changing. The Amazon is burning, the ice caps are melting, and the reefs are dying. What are the birds to do?

Many have begun the spiral toward extinction. Depending on how fast and how extremely the changes come, some will adapt, as they always have on the changing Earth.

The uneven pattern of evolution is normal. The biologist Stephen Jay Gould termed it punctuated equilibrium, long periods of relative stability “punctuated” by brief periods of rapid evolutionary change.

Generally speaking, when change comes fast, creatures with short generations do well. Bacteria, for instance, can “grow up” and reproduce–which in their case means divide in two–in as little as twenty minutes. The quick regeneration allows for more mutation and more rapid genetic development of adaptations to the new environment. We humans reproduce more slowly, so don’t do well by this measure. However, we are capable of considerable non-biological adaptation–say, build and operate an AC unit.

As for birds? So much depends.