Quick! They’re passing through just now, so this is the time: check your feeders, walk your woodlands! The cutest little sparrows of North America are dressed up and on the move!

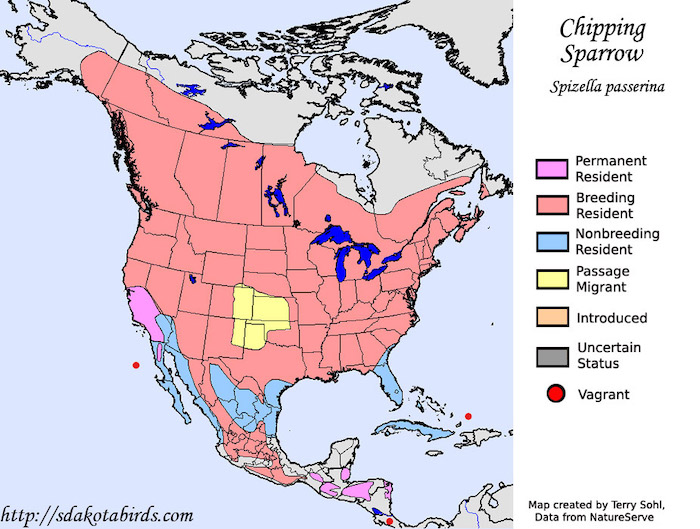

They’ve been in their winter browns, south of us and down into Mexico. But now the chipping sparrows have donned their red caps and broad white eyebrows. They are flocking up the Sacramento Valley and will nest in the mountains above us and northward far into Canada.

Look in the grasses among the oaks. Like other sparrows, “chippers” have the short, hefty bills designed for eating grass and weed seeds. But look in the trees, too. Insects are hatching out, and traveling sparrows are eager to load up on that high-protein fare.

And listen! Often traveling in small groups the birds keep in touch with one another and tune up for the breeding grounds with their song, a distinctive reedy trill on a single pitch.

A male will use that trill to stake out a breeding turf, usually in an open conifer forest. There he will vigorously chase off encroaching males–just as he will be chased from neighboring territories. Neither males nor females seem finicky about fidelity.

They are attentive parents, however. The female builds the nest, usually on or near the ground. It is a flimsy thing of grasses and soft fibers; it only needs to last about twenty-four days from eggs to fledging–even though the young hatch naked, blind, and weighing just one twentieth of an ounce. After a good start with the first fledglings the male typically continues to tend them while the female starts a second nest.

Chipping sparrows are common in their habitat from coast to coast, and number among the continent’s most numerous species, with population estimates up to 230 million. Still, they are not immune to changes in the world. Like other birds, their numbers have declined by about a third over the last fifty years, and now, like other birds, they are expected to be shifted northward.

There they will meet boreal forests that are being heavily logged for paper products. Efforts to keep the northern forests intact for chipping sparrows, numerous other feathered and furred creatures, and climate stability include consumer information about paper product sourcing. Our purchases impact these birds! Of widely available toilet paper, paper towels, and facial tissue, products from Green Forest consistently get high marks for their high recycled content. A substantial paper-product scorecard is available with an internet search of NRDC’s “The Issue with Tissue.”

Keep their nesting grounds intact, and look today for this red-capped cutie trilling buzzily as it passes through your neighborhood! It’s a spring treat!