It is the Thanksgiving season, and Redding has a special treat to appreciate. We have naturally what many cities spend a lot of money striving for: a place like Turtle Bay.

On any temperate morning, and many others too, the Bird Sanctuary Loop is the hub for a stream of cyclists, dog-walkers, joggers, retired couples, friends, young families, and bird-watchers. Children gaze at green-headed mallards and study the giant webs of garden spiders. Parents guide their children to the trailside as bell-ringing cyclists approach. Walkers watch jacketed fishermen float below them, their boats drifting, their lines in the water. In fall, when the weather is right, the trails and visitors can be showered with golden leaves.

This welcoming and well-traveled route lies in the heart of Redding, nestled inside a bend in the river that creates the maze of bywaters and peninsulas that, together with the main river channel, comprise Turtle Bay. The green and brindled landscape nurtures a complex of aquatic insects and snails, and the fish, river otters, birds, and fisherfolk they support. The riparian woods house red-shouldered hawks, woodpeckers, and the numerous birds that nest in the cavities they excavate. Quiet inlets make restful wintering grounds for geese and hundreds of ducks including mallards, ring-necks, shovelers, and teal. Herons and egrets stalk the shallows, and kingfishers plunge into clear pools. Out in the river’s main current golden-eyes dive for bugs while grebes and red-coiffed mergansers chase fish. At Turtle Bay nature quietly offers a fundamental experience of life–its giving and its taking back, its patterning and variety, its beauty.

But the wealth of Turtle Bay is not just the bend in the river. The bay is part of a corridor. Just as the Bird Sanctuary Loop is part of the larger River Trail, the Bay and its wildlife are part of the flowing water and the riparian woods, upriver and down. Each fall thousands of yellow warblers follow the river, scouring the riverside trees for insects to fuel their long flights to wintering grounds in Central America. Tanagers flock through, the males’ flame-red heads eclipsing into their yellow-greens of winter, as they gorge on the ripened grapes espaliered on towering cottonwood trees–again, fueling long flights south. Swallows–the orange-rumped cliff swallows that build homes under the Sundial Bridge, the shining blue tree swallows and violet-greens that nest in old woodpecker holes, and the rough-winged swallows that make homes in weep-holes at the Bella Vista water intake, all capture insects on the wing, skimming the river surface or circling high in the sky, first here where they hatch and then all along the river as they migrate. Redding’s famous eagles have fledged twenty eaglets at Turtle Bay; they, too, travel the corridor, both seasonally and a few years ago to try nesting downstream at Riverview Golf Course, where they fledged young but lost three nests before returning to their more reliable home at the Bay.

So far the Sacramento River corridor remains largely free of commercial development, allowing clean bywaters and riverine woods to grow the bugs that feed the fish and birds and other riparian life. Upriver from Turtle Bay the woods still flourish up to the dams, perhaps most broken at Redding’s Rodeo grounds, where the thin riverside forest has received a strip of welcome

replanting. Downstream, aside from the development along Park Marina Blvd, the riverbanks are substantially verdant.

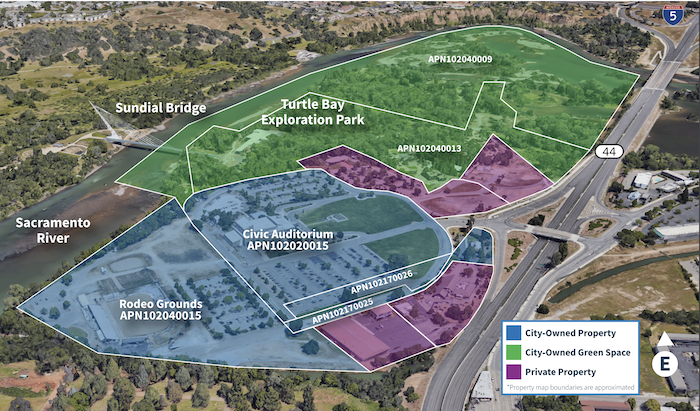

Now the city is considering selling land at Turtle Bay for commercial development. As this is written, the City Council is pursuing the land sale, while unofficially assuring that the Bird Sanctuary itself will be retained and spared the pavement, at least for now. Unfortunately, the biology of the Bay stands to lose regardless, because its life runs up and down the river.

City Council has seemed genuinely interested in getting public input: should the sights and sounds of riverside plants and wildlife be retained with permanent, broad setbacks for riparian woodlands? Should development be kept to areas that are already paved, perhaps diverted to Park Marina? Will a dressed-up Convention Center and more restaurants draw the revenue of visitors from the Bay Area and farther off? Ultimately, will selling riverine public lands for development improve the quality of life for citizens now and in the future? Your City Council wants to know what you value. You can reach them through cityofredding.org .