In 1993, the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center created International Migratory Bird Day (IMBD). This educational campaign focused on the Western Hemisphere and celebrates its 25th year in 2018. Since 2007, IMBD has been coordinated by Environment for the Americas (EFTA), a non-profit organization that strives to connect people to bird conservation.

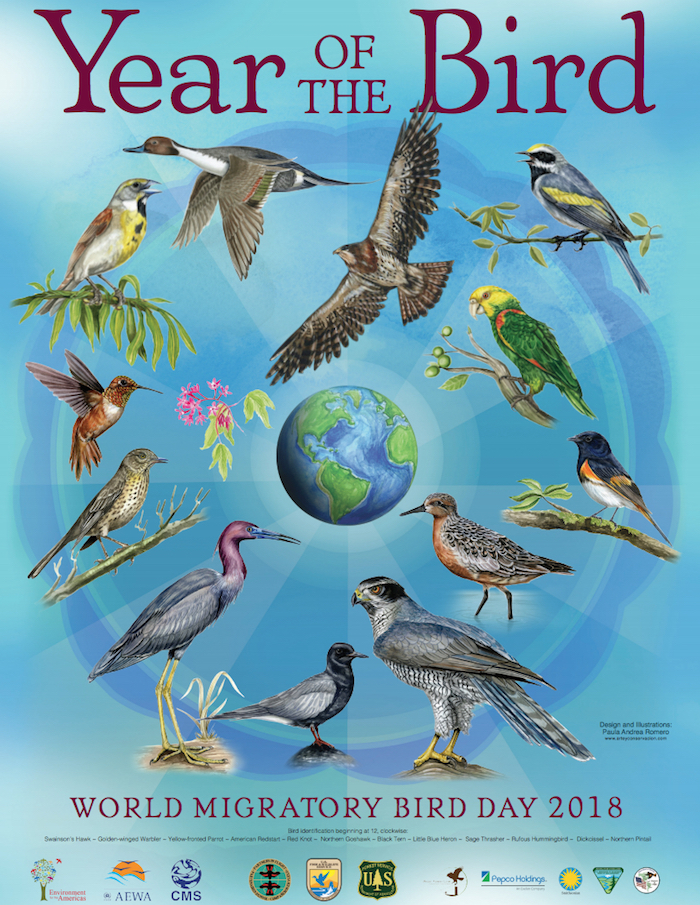

In 2018, EFTA joins the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) and the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) to create a single, global bird conservation education campaign, World Migratory Bird Day (WMBD). WMBC celebrates and brings attention to one of the most important and spectacular events in the Americas – bird migration.

Over the years, EFTA has made changes and improvements to International Migratory Bird Day. They developed the concept of a single conservation theme to help highlight one topic that is important to migratory bird conservation. Over the years, these educational campaigns have been integrated into numerous programs and events, focusing on topics including the habitats birds need to survive, birds and the ecosystem services they provide, the impacts of climate change on birds, and the laws, acts, and conventions that protect birds, such as the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the Convention on Biodiversity.

The Pectoral Sandpiper migrates from South America to the Arctic, a total return-trip of more than 30,000 km

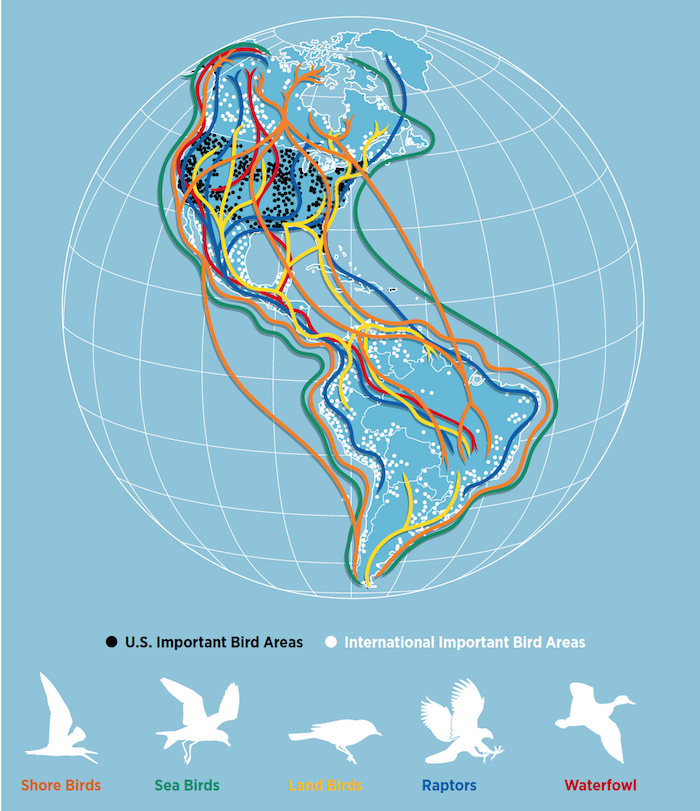

They also removed a specific date from the event. Once celebrated only on the second Saturday in May, they recognize that migratory birds leave and arrive at breeding and non-breeding states at different times, depending on many factors. They also stop at different sites across the Western Hemisphere to rest and refuel, providing opportunities to engage the public in learning about birds and their conservation. Today, they maintain traditional event dates on the second Saturday in May and the second Saturday in October, while encouraging organizations and groups to host their activities when migratory birds are present.

Nashville Warbler

Join us for a bird walk at Battle Creek State Wildlife Area and celebrate World Migratory Bird Day with Wintu Audubon!