McArthur-Burney Falls Memorial State Park sits on the eastern edge of the Cascade Range between two active volcanoes, Mount Shasta and Lassen Peak. The Cascade Range, part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, extends from Northern California to Southern British Columbia.

The park’s landscape was created by volcanic activity as well as erosion from weather and streams. This volcanic region is covered by black volcanic rock known as basalt. Created over a million years ago, the layered, porous basalt retains rainwater and snow melt forming huge subterranean rivers and reservoirs. One of these underground aquifers feeds Burney Creek and in turn Burney Falls, giving it a consistent flow of over 100 million gallons a day all year long.

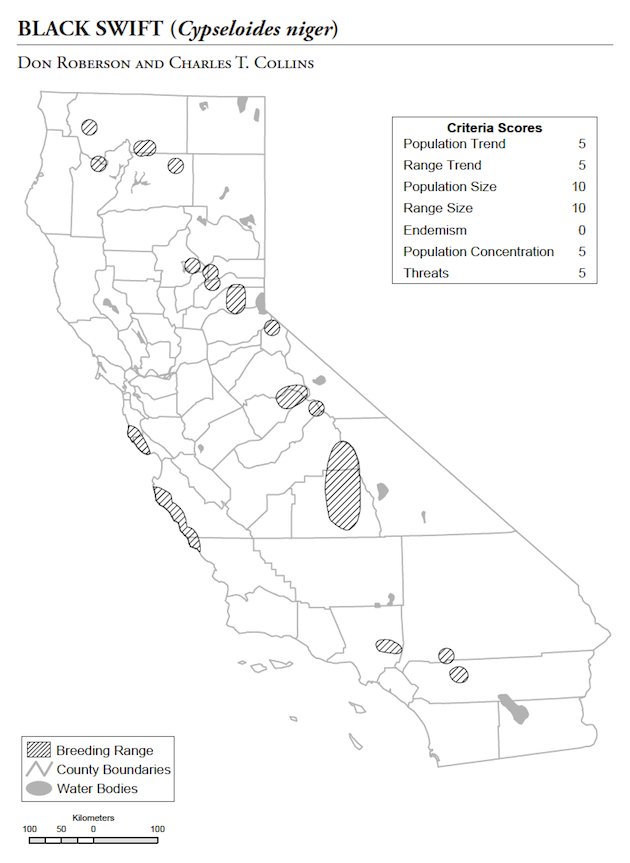

Undoubtedly one of the most interesting aspects of Burney Falls for birders is that it is one of the few locations in California where nesting Black Swifts (Cypseloides niger) can be found.

Photo from Wikipedia Commons taken by Terry Gray

Photo from Wikipedia Commons taken by Terry Gray

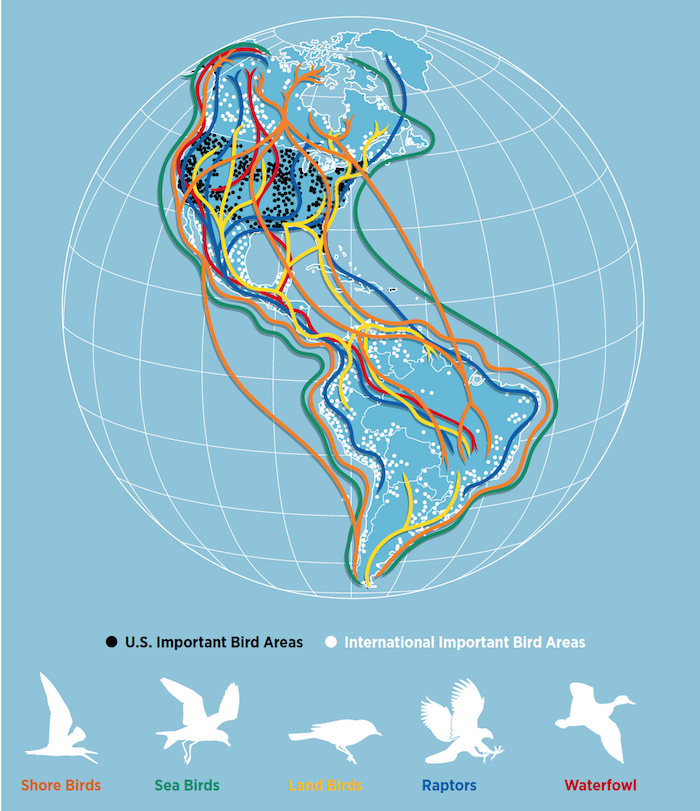

Even though the Black Swift occurs widely throughout western North America in summer, with its breeding range extending as far north as southeastern Alaska, as far east as central Colorado, and south through Mexico and Central America to Costa Rica, with additional populations in the West Indies, only about 80 specific nesting localities have been documented1.

The Black Swift is considered a Species of Special Concern in California. Even though the overall breeding range remains largely unchanged from that in the 1940’s, the entire coastal population has been in recent severe decline. The entire California population appears to be composed of perhaps 200 pairs at 40 to 45 sites2.

Fortunately, Black Swifts have high nest site fidelity and traditional nest-site use by swifts is common. Most Black Swift nest sites are regularly, if not always, occupied year after year though the recent declines in the coastal populations has been a mystery.

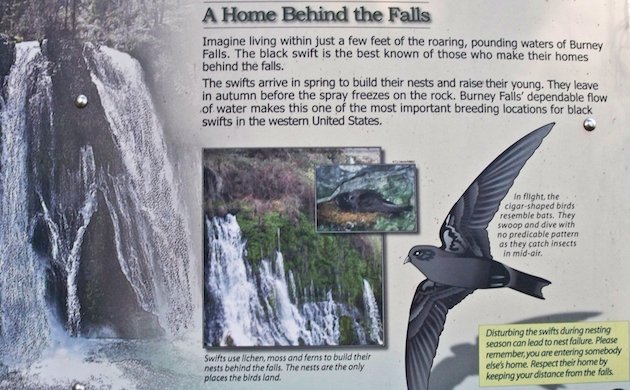

McArthur-Burney Falls Memorial State Park offers close viewing of these birds as well as interpretive signs throughout the park.

All of the following photos of Black Swifts were taken at Burney Falls by Glen Tepke who graciously gave me permission to use them (click on photos for full sized images).

Fortunately for me the Burney Falls Black Swift contingent consists of five to twenty pairs annually2. They can usually be seen foraging above the falls in the morning.

When I was there the first Black Swift I spotted was above the highest part of the falls heading down stream. It was obviously foraging on flying insects as it maneuvered through the air like a giant swallow with quick turns at the end of smooth arcing flights.

Apparently Black Swifts are in continuous flight when awake except when at or near the nest. I was closely observing this particular bird as it appeared and disappeared from my view until, all of a sudden, it appeared much lower and, banking down into the gorge, disappeared behind the falls into a small nest cave about a foot or two across.

These nest caves are described as “a niche on sheer rock cliffs, shaded and bathed in mist from the frigid splash of a nearby cascade often behind a rushing torrent of falling water and abundant spray1.”

This photo shows the location of the nest in relation to the full face of the falls.

Moss is the primary and sometimes only component used as nesting material by the Black Swift in inland locations. Pairs will also reuse the same nest in consecutive years, adding only a small amount of material to the nest.

The ecological requirements for Black Swifts to breed restrict them to a very limited supply of nesting locations.

Plus the fact that they only lay one egg per season which is incubated for about four weeks and the chicks don’t fledge for another fifty days gives you some notion as to why these birds are a Species of Special Concern.

This Black Swift with the white feather tips, photographed by Glen on the same day as the others above (July 5th), could be a juvenile or adult female but considering that they don’t usually begin nesting until the middle of May, it is most probably an adult female.

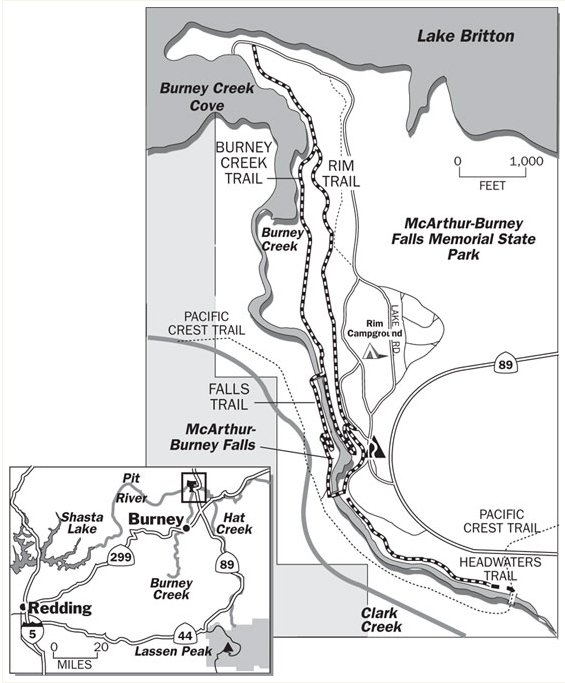

Of course Black Swifts are not the only reason to visit McArthur-Burney Memorial State Park. Over 130 bird species have been observed on the five miles of hiking trails that wind through evergreen and hardwood forests. The Pacific Crest Trail also passes through the park.

Burney Creek Trail follows Burney Creek through a forest of ponderosa pine, Douglas fir, incense cedar and a variety of oaks where American Dipper, White-headed and Pileated Woodpeckers, Red-breasted Sapsucker, Hermit, Black-throated Gray, McGillivray’s, Wilson’s, Nashville, Yellow-rumped and Yellow Warblers, Western Tanager, Cassin’s Vireo, Western Wood-Pewee, Evening Grosbeak, Steller’s Jay, Belted Kingfisher, Northern Flicker, Mountain Chickadee, Common Raven, Red-breasted and Pygmy Nuthatch, Brown Creeper, and Osprey can be seen, just to name a few.

A little over a mile from the falls, Burney Creek Trail terminates at a peninsula separating Burney Creek Cove from the main body of Lake Britton (see map above). This part of Lake Britton is actually part of the park and includes a boat launch facility at the cove and a sandy beach and swimming area on the lake.

Birds observed here include Common Merganser, Pied-billed, Western and Clark’s Grebes, Double-crested Cormorant, Great Blue Heron, Canada Goose, Bald and Golden Eagle, Red-tailed Hawk and Common Loon.

Nesting Purple Martins can also be found on the northwestern side of the lake and Vaux’s Swifts can be seen above the tree tops over the highway outside the park.

You can get more information on McArthur-Burney Memorial State Park by going to their website or downloading their brochure in PDF format.

References: 1Birds of North America Online, 2California Bird Species of Special Concern: A ranked assessment of species, subspecies, and distinct populations of birds of immediate conservation concern in California