The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation (NAMWC) is often held up as the best system of wildlife management and conservation in the world. Developed in the post-frontier era, the NAMWC helped put a stop to wanton wildlife destruction in an era where many species were being hunted and trapped ruthlessly to the brink of extinction.

But the tenets of the North American Model were developed in the 19th century, when wildlife ethics and science were a mere glimmer of what we understand today. The system was intended as a hunter-centric model, both guided by and benefitting consumptive interests.

Now, in 21st century America, we’re entertaining new considerations, in keeping with our modern understanding of wild animals and conservation. There is:

- Growing skepticism about how well the North American Model serves not just the wild animals in our public trust, but also the conservation priorities of non-consumptive users who are the majority users of public lands.

- Increased scrutiny of practices long considered the norm in wildlife management, including predator hunts, commercial trapping, the legal culling of non-game birds like American Crows, and some of the research protocols used to track and translocate wild animals.

- A new willingness among scientists to consider certain moral and ethical implications with respect to wild animals, where previously utilitarian ideas prevailed, including ideas of intrinsic value.

- Serious examination of the national funding paradigm and how it contributes to the conservation choices made on both federal and state levels.

New Ideas In Conservation

Thomas Serfass, a professor at Maryland’s Frostburg State University says, “I would describe the North American Model as incomplete. Federal funding has never been a prominent part of what’s been, or at least what’s been portrayed (as) the North American Model. Setting land aside in the public domain in perpetuity is probably the most substantive thing we do for wildlife conservation.1”

George Wuerthner, an ecologist and former hunting guide with a degree in wildlife biology, takes the debate a step further. In his piece on state agencies, The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation and Wolves, Mr. Wuerthner states, “Perhaps the most significant and obvious conflict between the goals of the NAMWC and actual behavior of state agencies has to do with management of predators, particularly bears, cougars, coyotes and wolves. State wildlife agencies have a financial conflict of interest that makes it impossible for them to manage predators with regards to the wider public values.”

This leads to obvious conflicts with the NAMWC prohibition against the frivolous killing and waste of wildlife. Given that few hunters actually consume coyotes, wolves, cougars, and except for a few individuals, even bears, it is obviously a “waste” of wildlife to shoot or trap these animals just for “fun”2.

Professor Marc Bekoff at the University of Colorado advances the even more progressive idea of “compassionate conservation.” Compassionate conservation describes an emerging field of interest which Bekoff describes in his book Rewilding Our Hearts:

“Compassionate conservation has become a popular new phrase and mind-set over the past few years, one that has increasingly informed global efforts to conserve species and restore ecosystems. Compassionate conservation’s central premise is that every individual animal’s life counts, so our attempts to repair ecological damage or save a certain species, shouldn’t, by design or accident, sacrifice or negatively impact even more life in the process.”

In Coyotes, Compassionate Conservation and Coexistence, Camilla Fox, founder of Project Coyote, echoes this perspective as it relates to predators: “Greater understanding of the ecological importance of native carnivores and increasing public opposition to lethal ‘control’ have led to a growing demand for humane and ecologically sound conservation practices.”

These voices come together on the central point that the North American Model is falling short in critical ways, that it’s outdated when juxtaposed against more progressive ideas in conservation, and that it’s time to seriously consider the shortcomings of our current paradigm while pushing for positive changes that can inform wildlife conservation decisions into the next century.

A significant part of that transformation is recognizing the substantive blocks to change. And among the most important factors is funding and how the funding apparatus is tilted toward preserving the status quo.

As George Wuerthner says with respect to predator control, “In most cases hunters perceive predators as detrimental to hunting—even though there is plenty of evidence that predators seldom depress wildlife populations across the broader landscape. As a result of the funding mechanisms whereby state agencies rely on hunter purchase of hunting tags to maintain operations, these bureaucracies are not going to promote predators in the face of opposition from hunters.”

Consumptive & Non-consumptive Users

Non-consumptive users are accustomed to hearing that conservationist hunters not only fund wildlife endeavors but were also the primaries in early North American conservation efforts. For example, Theodore Roosevelt’s environmental victories are often cited without comparable mention of non-hunter John Muir’s critical influence over Roosevelt’s thinking on ecology, wildlife and environment. As such, non-consumptive users have historically been viewed as lesser stakeholders in wildlife management decisions.

But is there validity to these commonly held ideas?

Michael P. Nelson, a Professor of environmental philosophy and ethics at Oregon State University, points out that recreational hunting was only one of several important factors that led to improved conservation in North America. He notes that “Beginning in the 1960s, for example, conservation was dominated by non-hunters whose legacy includes key legislation such as the U.S. Wilderness Act, Endangered Species Act, Clean Air and Water Acts, and similar acts in Canada. In addition, what are commonly referred to as “non-consumptive” uses of nature—such as national park visitation and bird watching—have also been important for motivating conservation action. These perspectives on the history of conservation do not stand in opposition to hunting, yet they show how other forces also shaped North American wildlife conservation, and how hunting is not necessary for conservation3.

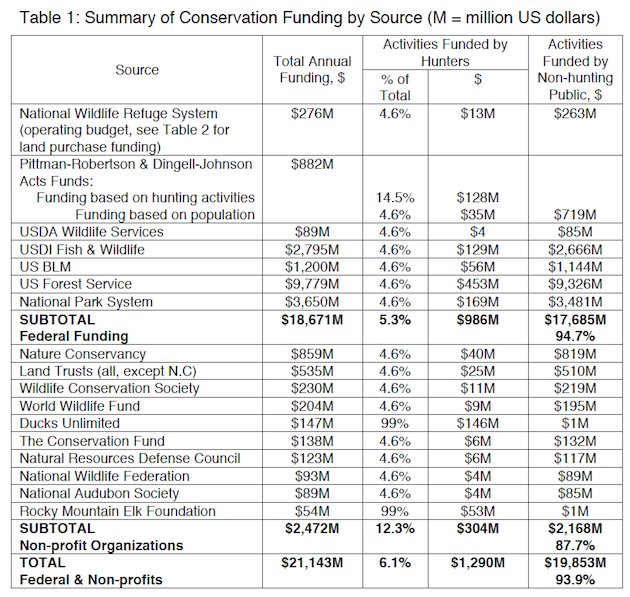

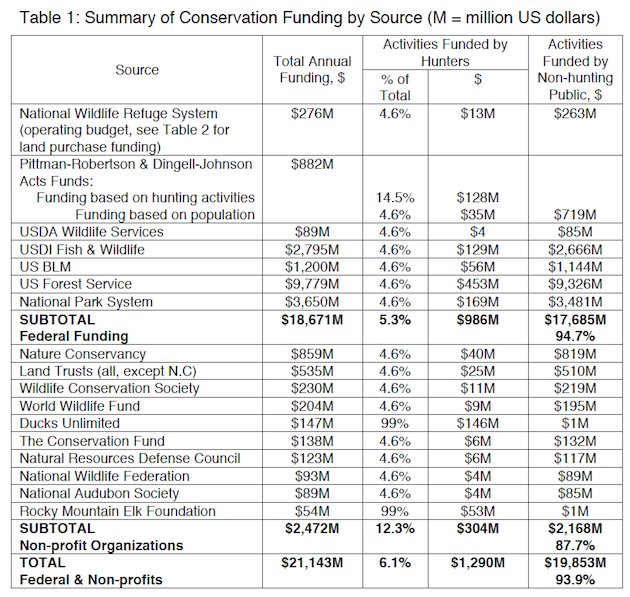

A new study authored by Mark E. Smith and Donald A. Molde, shows that approximately 95% of federal, 88% of non-profit, and 94% of total funding for wildlife conservation and management come from the non-hunting public. The authors contend that a proper understanding and accurate public perception of this funding question is a necessary next step in furthering the current debate as to whether and how much influence the general public should have at the wildlife policy-making level, particularly within state wildlife agencies4.

Smith and Molde state that “Sportsmen favor the current system, which places a heavy emphasis on their interests through favorable composition of wildlife commissions and a continued emphasis on ungulate management.” They agree with George Wuerthner saying, “Nonhuman predators (wolves, mountain lions, coyotes, ravens and others) are disfavored by wildlife managers at all levels as competition for sportsmen and are treated as second-class citizens of the animal kingdom. Sportsmen suggest this bias is justified because ‘Sportsmen pay for wildlife,’ a refrain heard repeatedly when these matters are discussed. Agency personnel and policy foster this belief as well.”

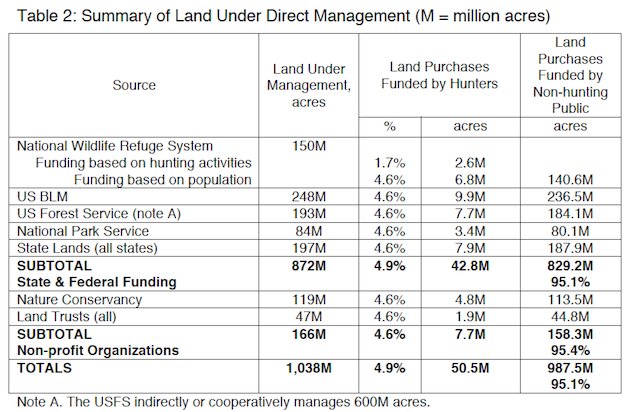

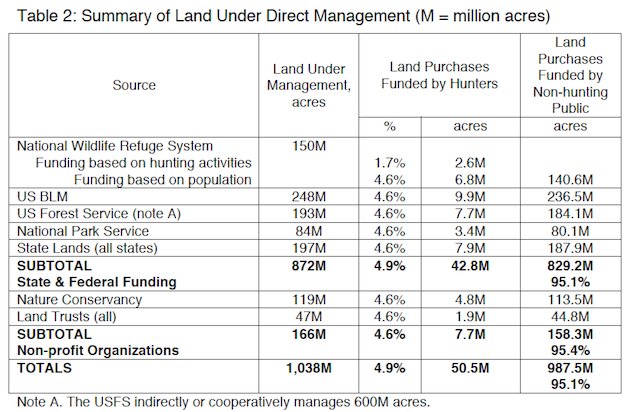

“Funding of wildlife land gets a lot of attention among both sportsmen and other outdoor enthusiasts. Considering the four main federal agencies, the combined state-owned lands, and the collective non profits falling in the category of land trusts, there are 1.038 billion acres of wildlife habitat under conservation management, of which about 4.9% were funded by hunters and 95.1% funded by the non-hunting public.”

The Public Trust Doctrine (PTD) is the principle that certain resources are preserved for public use, and that the government is required to maintain them for the public’s reasonable use. Modern wildlife management has wandered far from the original path of this doctrine and the NAMWC from which it flows. Felix E. Smith, a veteran fish and wildlife biologist, identified three criteria that need to be met for the PTD to be effective:

- The general public must be aware of their legal standing with respect to public ownership of wildlife

- This standing and the rights associated with it must be enforceable against the government so that the public can hold it accountable

- Interpretation of these rights must be adaptable to contemporary concerns, such as biodiversity and species extinction.

All three are impaired when the basis of public debate is a myth. It’s time that we call for honest dialog from our state and federal agencies and transparency in wildlife policy making.

There is a new movement to reinvent wildlife conservation in the 21st century for sustainability. Dr. David Lavigne, Science Advisor to the International Fund for Animal Welfare, co-authored Gaining Ground: In Pursuit of Ecological Sustainability5. He puts forward these Principles of Wildlife Conservation for the 21st Century:

- Wildlife has aesthetic, cultural, ecological, economic, intrinsic, recreational, scientific, social, and spiritual values that need to be acknowledged, preserved and passed on to future generations.

- Recognizing that wildlife has intrinsic value broadens conservation to include both individual animals and the populations they comprise. In other words, 21st century “geocentric” conservation must be concerned about the welfare of individual animals (traditionally termed animal welfare, or animal protection) and the welfare of wild populations (the traditional focus of progressive conservation).

- As a consequence, “people should treat all creatures decently, and protect them from cruelty, avoidable suffering, and unnecessary killing.” This principle reaffirms that animal welfare is an integral part of modern conservation.

- Conservation measures that compromise the welfare of individual animals to achieve goals at the level of the population should not be the preferred means of addressing wildlife conservation issues.

- Capturing wild animals for live trade and captivity should not be permitted. Bringing individual wild animals into captivity for short periods may be permitted, however, to deal with animal welfare issues such as disease, injury or estrangement.

- All attempts to domesticate wild animals should be discouraged.

- Efforts to protect and conserve wildlife and wildlife habitat should begin long before species become rare and more costly to protect.

- The maintenance of viable wildlife populations and functioning ecosystems should take precedence over their use by people.

- Recreational and other uses of wilderness must not compromise the very essence of “wilderness” as untrammeled wild lands, and any such uses should be compatible with this basic principle.

- Wildlife belongs to everyone and no one. It is protected and held in trust for society by governments or appropriate intergovernmental conventions (i.e. central management authorities at an appropriate scale).

- “Highly migratory species” belong to all nations and not just those that wish to exploit them.

- Effective conservation of wildlife relies upon a well-informed and involved public.

- Any material benefits derived from wildlife must be allocated by law – following consultation with the public, who collectively “own” the resource – and not by the marketplace, birthright, land ownership, or social position.

- All individuals share the costs of conserving wildlife. Those whose actions result in additional costs should bear them.

- The onus must be on those who wish to use nature and natural resources, e.g. exploiters and developers, to demonstrate that their actions will not be detrimental to the goal of achieving biological and ecological sustainability.

- The exploiter/developer pays. Those exploiting wildlife should bear the full costs of ensuring that any exploitation is ecologically sustainable, including the cost of enforcing any catch limits, and any scientific research

required to determine those catch limits. Exploitation (and depletion) of wild living resources should no longer be subsidized by governments.

- The use of wildlife for subsistence purposes by human populations should not be equated with their commercial consumptive use.

- Use of wildlife and ecosystems should be frugal (parsimonious) and efficient (not wasteful), ensuring that any use is biologically and ecologically sustainable. (Parsimonious use means taking as little as you need, rather than as much as deemed possible as implied, for example, by the idea of maximum sustainable yield.)

- Human development should not threaten the integrity of nature or the survival of other species.

- Development of one society or generation should not limit the opportunities of other societies or generations.

- Each generation should leave to the future a world that is at least as biologically and ecologically diverse and productive as the one it inherited, and – given the current state of the planet – a world in which the physical environment (including the land, water, and atmosphere) is less polluted than the one it inherited.

- The establishment of protected areas – where human impacts, including exploitation and development, on wildlife and their habitats are reduced to an absolute minimum – is an essential component of any plan to achieve biological and ecological sustainability.

- Ultimately, human use of nature must be guided by humility, prudence, and precaution.

The fathers of the conservation movement – including Gifford Pinchot and Aldo Leopold – have been dead now for more than 50 years. The conservation and environmental movements to which they contributed so much have been losing ground for the past 30. Dr. Lavigne concludes that to bring about the future, all conservationists should aspire to necessitate the creation of a New Conservation Movement, dedicated to gaining ground in the pursuit of ecological sustainability, and focused on the acquisition and use of political power to achieve it.

###

The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation is composed of seven focal points:

- Wildlife as Public Trust Resources – Wildlife is a public trust and must be managed for all citizens. No one can “own” wildlife

- Elimination of Markets for Game – Commercial hunting of wildlife is prohibited (but not trapping which is one of the obvious contradictions in the model)

- Allocation of Wildlife by Law – Public participation is essential in development of wildlife management policies

- Wildlife Should Only be Killed for a Legitimate Purpose – A philosophical and legal ban on wasteful and frivolous killing of wildlife

- Wildlife Are Considered an International Resource – As wildlife do not exist only within fixed political boundaries, effective management of these resources must be done internationally

- Science is the Proper Tool for Discharge of Wildlife Policy – Wildlife must be managed using fact, science and the latest research

- Democracy of Hunting – The right to hunt in the United States and Canada by all citizens of good standing

References: 1Wyofile “Study: Non-hunters Contribute Most to Wildlife”, 2North American Model of Wildlife Conservation And Wolves, 3An Inadequate Construct? North American Model: What’s Flawed, What’s Missing, What’s Needed , 4Wildlife Conservation & Management Funding in the U.S., 5Gaining Ground: In Pursuit of Ecological Sustainability